In March 2012, Islamic fundamentalists banned music in the West African nation of Mali. I spoke to Aliou – lead singer of Songhoy Blues – about the power of music in Mali and their international success following the crisis

In the vast, landlocked country of Mali in West Africa, music holds social and political importance to a greater extent than in any other country. With a literacy rate of just 33%, it is through music that Malians exchange information, learn about their history and come to know their own identity. Music was a primary tool used by post-independence elites to construct a national identity in the 1960’s; and thegriots – traditional praise singers – are the repository of Mali’s past, providing Malians with an aural repertoire of its proud history and culture. As one of the world’s poorest countries, music is Mali’s main export, and its musicians are essentially cultural ambassadors. Musicians are the voice of Mali.

What happens when a nation loses its voice?

In March 2012, combined forces of Tuareg separatists and Islamic fundamentalists seized control of Mali’s Northern region, declaring an independent state of Azawad. At this crucial moment, Islamist groups ceased their alliance with the separatists, and attempted to create an Islamic state with the implementation of hardline Sharia law. By August, Mali’s renowned tolerance, cultural diversity and religious freedoms no longer prospered. The Islamists declared “we do not want Satan’s music”, henceforth banning all musical forms other than Qur’anic chants. The following ten months saw the silencing of musicians in Mali’s vast Northern region and the precautious dwindling of musical activity in the South, as militias proceeded to set alight instruments, cassettes, musical archives and destroy recording studios and radio stations. Musicians and listeners alike lived in fear and trepidation, as accounts testify:

Khaira Arby, hailed as “The Voice of the North”, was forced to flee to the South as militants threatened that, when she returns to her home “they will cut out [her] tongue”.

“A group of teenagers sat around a ghetto blaster listening to Bob Marley…Islamic police came by and seeing the reggae fans, stopped and accosted them. ‘This music is haram! – forbidden by Islamic law – said one of the Islamists as he yanked the cassette out of the blaster and crushed it under his feet.”

As musicians were among the 500,000 who fled to the South or to neighbouring countries, the region was left devoid of its music, and therefore, devoid of its voice. “Everything in Mali is transmitted through in music”, stated Manny Ansar, organiser of the world-renowned ‘Festival in the Desert’. “Mali without music is impossible”. Such emphatic statements, though not exaggerated, are evidential as to why the Islamists specifically targeted music. They are destroying all memory, history and tradition, breaking a crucial means of social cohesion, in order to impose their own ideal of an Islamic state. Malians were left without a means to practice their culture, and their sense of identity was at risk without its primary medium of expression. Further, without means for cultural exchange, tensions grew between the country’s ethnic groups and a North/South divide began to emerge, fuelled by underlying suspicions of the Tuareg, whose separatist movement sparked the crisis in the first instance.

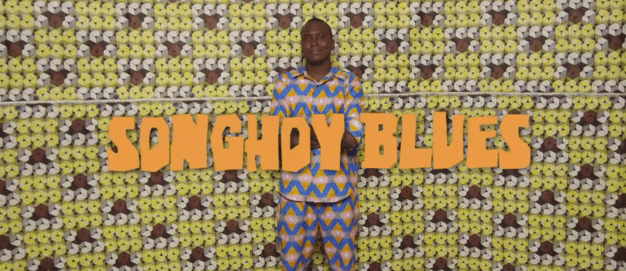

The paradoxical outcome of this musical silencing, though, has been to raise the voice of those exiled Malian musicians, who are using music to fight back. In many ways, the plight of Mali’s musicians has elevated international awareness of the crisis, fuelled by fascination. Had it not been for the country’s world-renowned music culture, outsiders would likely view the country as it does other sites of conflict, in terms of bewilderment, horror and helplessness. International figures including Bono and Damon Albarn have spearheaded the recent drive to afford attention to Malian music. Probably the most successful of those to emerge from this has been Songhoy Blues, comprising of four musicians from the North who formed a band after they fled to the country’s capital, Bamako, and sought to bring a piece of their Northern homeland to fellow refugees living in the South. They began to tour the Bamako club circuit, playing small venues with an audience comprised of both Southern and Northern people. When I spoke to the band’s lead singer, Aliou, he highlighted the importance of this:

“It brought people together, it didn’t matter if you were from the South of the North, or you were a Tuareg or Songhoy, the most important reason to be there was the music”.

The band’s touring stint within Bamako did not last long, though, as they soon caught the attention of Damon Albarn’s Africa Express project, proving successful in their audition and teaming up with Nick Zinner (of the Yeah Yeah Yeah’s) who would produce their album, ‘Music in Exile’. Songhoy Blues are now signed to Transgressive Records (home to Foals, Bloc Party & Johnny Flynn), they have appeared on Later Live with Jools Holland, toured Europe, and even played Glastonbury. Indeed, several Malian artists have since the ban graced the stages of Glastonbury, including Rokia Traoré and Fatoumata Diawara. I asked Aliou what kind of impact he thinks the band can gain from this international success:

“For us, the challenge is to spread Malian music and the Malian culture, to talk about what is going on in Mali and to talk about our story”.

Songhoy blues have thereby used their elevated position as musicians, which contradictorily emerged from the music ban, to act as a voice for their fellow Malians and to keep their culture and identity alive. Just as important, though, is the fact that the lyrics are sung in the band’s native language, and contain important messages to those back home. For example, the first song in the album, ‘Soubour’, is about patience: “People were so badly impacted by the crisis in the North…we wanted to to send a call to all those stressed people to be patient”. ‘Désert Mélodie’ was written during the crisis, and reflects the bands’ desire to write songs that brought relief to people’s spirits rather than turned people against each other. It calls on Malians to find peace and unity: “Once upon a time Mali was a land of unity / Today in Mali, they want to divide us / Mali we are all the same”.

Herein lies the greatest importance of music in Mali today: since French forces eradicated Islamist rule and the music ban was lifted in January 2013, Malians have become increasingly disillusioned with a corrupt and ineffective government. And so, they are more likely to listen to the country’s musicians rather than its politicians. Musicians are Mali’s true ambassadors; they are, louder than ever, the voice of the country. During the battle for the control of the North in 2013, singer Fatoumata Diawara gathered a group of more than 40 Malian musicians together to record a song entitled ‘Mali-ko’(‘Peace’). Diawara emphasised that “The Malian people look to us. They have lost hope in politics…people are looking up to musicians for a sense of direction”. The lyrics ask”: “What has become of beautiful Mali?”,and encourages Malians to “Unite as one”.

It seems that the crisis in Mali did have a silver lining for some, as various Malian artists have gained exposure and success on an international scale. However, as instability and tensions remain in the North today, the international success stories are incapable of doing much good within the country itself. In November 2015, 20 were killed by Islamists a shooting at a hotel in Bamako; and in January 2017, 77 were killed in a bombing at a military camp in Gao (in the North). The country is now embroiled in a dispute with a complex religious dimension, in which musicians occupy a precarious position. The question of music’s place in Islam is a controversial one, and the traditional role of music as an accompaniment, or indeed as an important medium, of social and political relations is no longer as significant as it was prior to 2012. Musicians have, at best, provided a voice for Malians to seek refuge and direction in the face of an unprecedented and protracted crisis, and have done much to promote the culture of their embattled country. But music’s potential as an important tool for reconciliation – as a traditional means of social cohesion, to bring people of all ethnicities together – has been hindered by the religious complexities that now characterise the country’s instability.